This weekend, friend of the Report,

, and I co-chaired a panel on “regard” at the American Comparative Literature Association’s annual conference. Tia reached out to me last summer about co-chairing the panel and I’m really glad that I agreed to do it. When Tia and I worked on the call for papers, we were focused on regard as a practice of careful looking and attention that could extend to critical/scholarly acts of reading. The papers that ended up on the panel took those notions and took it further, thinking about the slippage between the self (the ‘I’) and seeing (the eye), as well as acts of beholding while in states of precarity. As a good conference panel should, all the papers expanded what I understood regard to be—not just an outwardly look or gesture towards another, but the look that is or cannot be returned; the unreturned or disrupted look as an act of self-regard. It also made me think about how even careful attention can be obscuring and how mutuality can be transformed into something more parasitic.You may recall that I wrote about “regard” last summer in regards to Cauleen Smith’s Drylongso. I’m now at the beginning stages of writing a dissertation chapter about that movie and how it depicts the young Black woman’s mobile gaze, as well as other Black femme-created cinema in the 80s and 90s that stage acts of Black femme mobility. This brief reflection by Smith in SEEN magazine1 about the making and marketing of the movie really resonated with me, particularly her comment on feeling defensive the whole time she was promoting the movie because it didn’t fit what people expected or demanded for Black movies at the time.

I taught W.E.B DuBois’ short story, “The Comet,” this past semester so I was excited when friend of the Report,

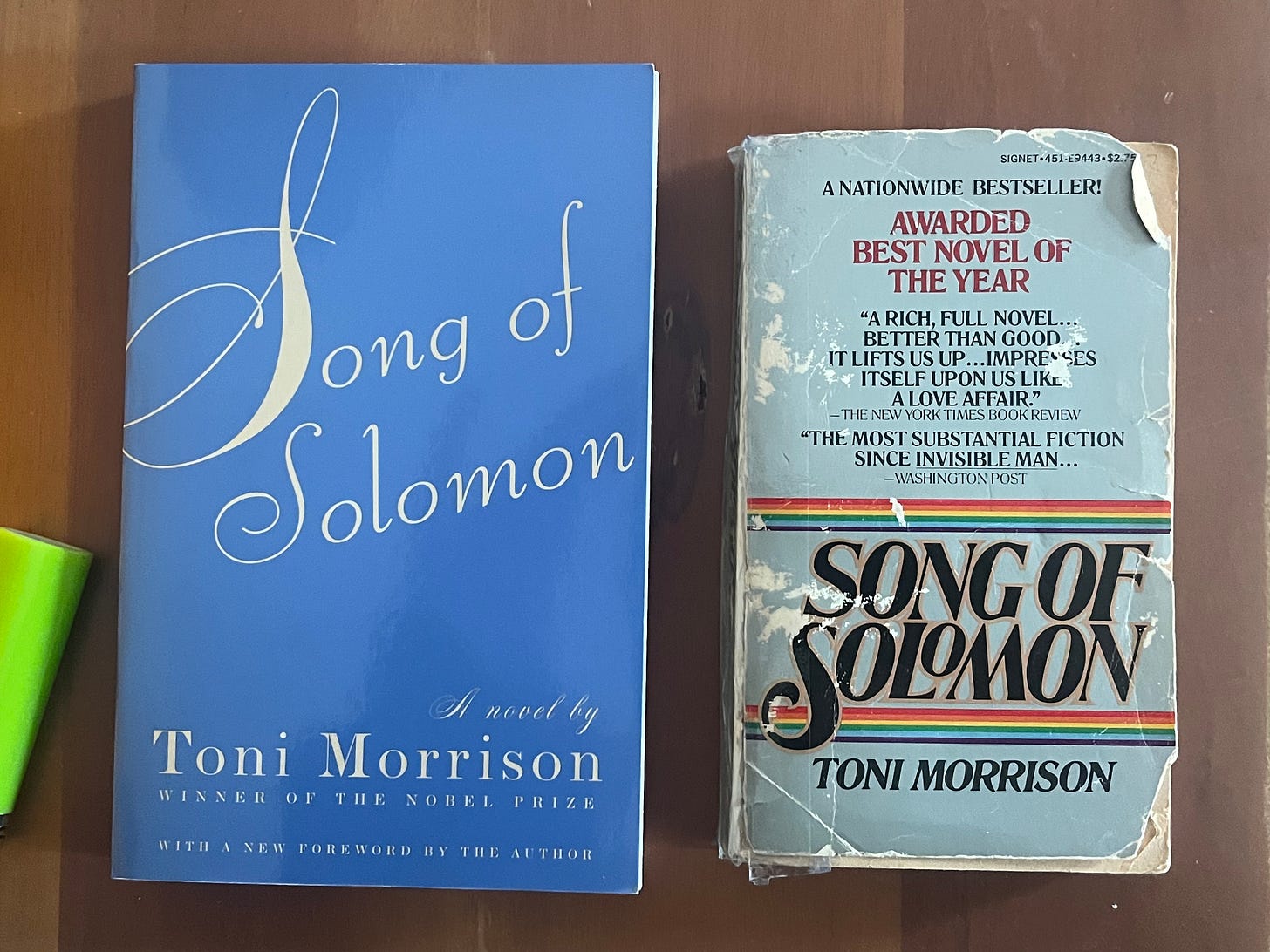

, shared Saidiya Hartman’s 2020 essay on the story, “The End of White Supremacy, An American Romance.” “The Comet” is a speculative, sci-fi story in which a comet hits New York, killing everyone but a Black bank messenger, Jim, and a wealthy white woman. As the sole survivors of the catastrophe, it eventually becomes evident that they will be tasked with continuing the human race. It’s a vision of interracial affinity (Du Bois writes in the story that what rises between them as they come to terms with their task is “was not lust; it was not love”) as a gateway to a new world, one in which white supremacy does not exist. Just as they are about to make their commitment to this future, the couple is interrupted by the honk of a car horn. It turns out that they’re not the last survivors—the woman’s father and fiancé are still alive and they burst upon the couple as they’re about to join hands on the rooftop of the MetLife building. As the world roars back to life, the “dream” of interracial affinity dies. But Hartman is less interested in the lost image of interracial intimacy and instead turns to the brief image of Black love that closes the story. It is the image of between Jim and his unnamed wife, the mother of his child, and their child, who now lays dead in his mother’s arms. Hartman reads the dead child as a symbol of the impossibility that this black love can have any kind of legacy, any kind of future. Black love can exist in the moment—in moments—but cannot be renewed or passed on. For Hartman, the question of Du Bois’ ending, and many other depictions of Black love is this: “How is love possible for those dispossessed of the future and living under the threat of death? Is love a synonym for abolition?”Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon was the only work of fiction I completed this month. I read it half for enjoyment, half for research, and while I thought it was mostly brilliant—it’s Toni Morrison, I mean c’mon—I’m still annoyed and unconvinced by the ending! For me, the ending undoes or disrupts the world of the novel that Morrison sets up throughout, even as it is basically a satisfactory conclusion. I’m trying to not think of this as a fault of the novel but rather as opening for thinking about the novel’s goals differently, especially in relation to her other texts. (I’m actually trying to think of it in relation to Timothy Bewes’ Free Indirect: The Novel in a Postfictional Age, but that book was so stressful to read the first time, I’m reluctant to return to it.) Part of my dissatisfaction with the conclusion is the way it affirms the treatment of women in the novel as the catalysts for, and the grounds on which, the male protagonist achieves self-consciousness and enters into a legitimate manhood that earns him his position as head of the family (leader of the race). So I’m trying to consider if the formal disjunction of the conclusion can be connected to the “intersectional” role (as in the necessary gaps or spaces that allow for the protagonist’s cohesiveness) of women in the novel.

I know the Met Gala is old news now but I have to shoutout Lynette Nylander’s episode of How Long Gone all about the Gala’s red carpet. Although they didn’t end up getting into this in the episode, Lynette made an important point about how “black dandy” is not synonymous with “black stylish man,” a distinction that I noticed was not being made in much of the conversation around the significance of the exhibition. I’m planning to go to the exhibit some time this week, so I’ll be interested to see how it comes up there in relation to the questions of class and respectability that the black dandy raises.

Quick notes: I can’t believe I’m saying this but Chinatown and The Godfather (both first time watches) were my favorites of the movies I watched this month. The new HAIM single, “take me back,” sounds like something you’d hear in an H&M commercial in 2010 (complimentary). Romy Mars’ first few singles didn’t really do it for me but “A-Lister”—an Addison song if Olivia Rodrigo sang it—is pretty perfect. Speaking of Addison: “Fame is a Gun”? In the words of “headphones on,” I’m “gonna dance, gonna dance”!

I’d never heard of SEEN, which is a magazine focusing on Black, Brown, and Indigenous film an visual art but I have a subscription now.